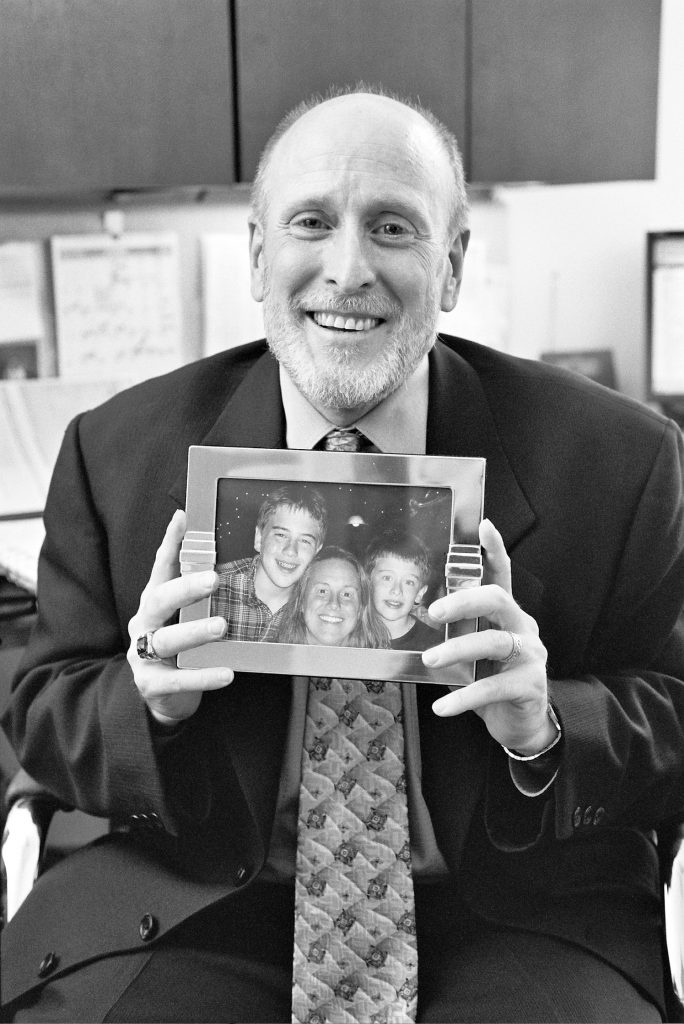

My cancer diagnosis came as a complete surprise to me.

I’d led a pretty healthy life and hadn’t had any major medical issues prior to my diagnosis. I had been in a phase of my life where I was focusing on exercise and weight reduction. I had lost a good amount of weight and I just thought my plans were going well. But it seems my weight loss was a symptom, not a result.

I had scheduled a regular physical, and the doctor asked for a blood test. The test came back unusual, with a high white blood cell count. I knew from my work at the Cardinal Bernardin Cancer Center of Loyola University Chicago that this could be associated with cancer. I recognize the irony of being an administrator at a cancer center and having a “surprise” diagnosis of cancer.

I was 47 at the time, and spent most of the next few days in shock.

My diagnosis was CML, chronic myeloid leukemia, which is a cancer of the blood cells. I got into a clinical trial for a drug, which worked for me for a while, but then stopped being effective. After that, the only feasible option for me was to have a bone marrow transplantation (BMT).

Most doctor-patient conversations about cancer are extremely serious and the questions being considered are about life and death. At the time of my diagnosis and contemplating a bone marrow transplant, I wouldn’t have thought to ask, “How disabled might I be afterwards?” or even about the risk of subsequent cancers. Questions about quality of life and physical complications are a secondary concern at such times.

Most doctor-patient conversations about cancer are extremely serious and the questions being considered are about life and death. At the time of my diagnosis and contemplating a bone marrow transplant, I wouldn’t have thought to ask, “How disabled might I be afterwards?” or even about the risk of subsequent cancers. Questions about quality of life and physical complications are a secondary concern at such times.

That’s why I was excited about the concept of working with PCORI, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and their focus on incorporating patient input into research. From my work, I had some familiarity with PCORI, and knew that they are an organization that focuses on comparative effective research, essentially, what treatments or therapies work best. What makes PCORI unique is that they involve patients in every step of the research process, from formulating questions, to the research itself. The world of research, from my previous perspective, was one of looking for better therapeutic alternatives, of how to treat more people with less morbidity and mortality. The question of how it impacts the patient and the patient’s family was secondary.

The thought of PCORI coming in and saying, what’s the patient’s viewpoint, what is important to them, has been an interesting and fascinating perspective. It goes beyond clinical focus and recognizes important questions like emotional impact and lifestyle. It’s definitely something to be conscious of because clinicians are used to looking at science and numbers, but the patients are looking at something entirely different. Younger patients diagnosed with cancer have questions about fertility and sexuality that I wouldn’t have thought to ask about. But now I know the importance of having that kind of follow-up conversation. When you’re grappling with this life and death issue, just knowing that the doctor is already talking about ‘long term” could make a patient feel more optimistic about success.

The PCORI-funded project I worked on brings people who have had bone marrow transplants, and their family members or caregivers, together with doctors and researchers, to discuss what information about BMT was most important to them in making treatment decisions. The goal is to provide information about the outcomes of BMT from the perspective of the patient, and decide which research questions are most important to patients and doctors, as well as the best time and way to provide that information.

By and large, I had what I would call a relatively easy transplant. My side effects have been relatively minor, and rebuilding my immune system occurred relatively quickly, compared to many. While physically I believe I’ve recovered, it. Having cancer and having had a bone marrow transplant is an ever-present awareness to me and my family. It’s the first thing I think of whenever I encounter something new, especially whenever I get sick.

One of the gifts, however, of surviving something like this is the realization that I had one of the worst things that could happen to someone, and my family and I got through it. I KNOW that anything else that happens in life, we can handle.